My girlfriend and I watched Good Will Hunting recently.

It tells the story of Will Hunting, an off-the-charts genius, and his soul-crushing dilemma. Remain true to his roots and have a fine, normal, happy life with his hoodlum friends? Or set sail to maximize his potential instead — take the road fraught with failure, loneliness, difficulty, and pain, but with a ton more self-actualization on the way and possibly even world-renowned greatness at the end?

I’ve always been fascinated by the tension between needing to make the most out of life and being content with an ordinary, good-enough existence.

Some questions that keep me awake at night: Does long-term life-satisfaction require you exert yourself to fulfill your potential? Is there something wrong with not ambitiously developing your gifts? Or, alternatively, do strong desires for success merely spring from boredom-avoidance?

In this essay, I explore several ideas from Will’s journey that stopped me and challenged me.

Changed me.

“An increasingly mediocrity-hostile zeitgeist”

One of my favorite bloggers, Ribbonfarm’s Venkatesh Rao, has written extensively about how we live in an “increasingly mediocrity-hostile zeitgeist.” Here’s mathematical proof for that proposition:

Mediocrity is the opposite of excellence. By definition, excellence (performing far above the average) is exceptional. However, it’s also becoming the norm (expected as average performance). A self-contradictory trend. The average can’t be above-average.

Society’s expectations soar and become unattainable to the majority.

Let’s give this a fancy name: the normalization of perfection.

How to be a normal human being in 2019:

- Super awesome career and CV

- Super awesome social life

- Super awesome sex life

- Super awesome body

- Super awesome amount of Instagram followers

In a meritocracy, being ordinary says something about you: “Ya basic”

It’s not just that these demands are rather high. We’re also told we all have the potential to meet them.

The perfect life — encapsulated by achievement, wealth, and social status — is available to anyone, provided you try hard enough.

We’re told that, to introduce another label, we live in a meritocraticcivilization: a society in which everyone is graded, the good at the top, bad at the bottom, exactly as it should be. Your position on the social ladder is a direct and fair result of your value.

Since we can, the thought continues, we ought to be perfect. Otherwise we suck, and contempt awaits us.

“Ya basic.”

The rat race isn’t optional

We all get judged.

That’s why today’s scornful emphases on excellence are a product of our culture, rather than instances of condescending personalities.

When people wear “f**k mediocrity 😠” t-shirts, they’re not necessarily assholes. They just want to be loved.

This link may seem unexpected, but it’s actually not hard to trace a line from (a) our meritocratic society to (b) folks practicing an anti-mediocrity religion to get intimate needs met.

As psychologists Thomas Curran and Andrew Hill argue in their paper Perfectionism Is Increasing Over Time: A Meta-Analysis of Birth Cohort Differences From 1989 to 2016:

Bowing for the altar of anti-mediocrity is a survival strategy in a society that links certain emotional rewards — love, respect — to being above-average.

Here’s the step-wise connection:

- We think the perfect life is attainable for all. There is a deterministic, learnable relationship between striving and success; between legible merit and desirable outcomes.

- We believe the poor achievement of those who do not reach such heights reflects their low personal value.

- These pressures place a strong need for people to strive and achieve.

- We respond by having increasingly unrealistic expectations of ourselves. We go: perfect is the new normal, so that’s the standard I should hold myself to. In a world where actual mobility is both difficult and strongly dependent on luck, but there is a widely performed false narrative of pure meritocracy, it pays to signal apparent control over your destiny.

- As everyone imposes more demanding standards, we feel perfectionism is necessary to feel safe and of worth.

- As a result, we display perfection to secure love and respect. We engage in, Curran and Hill write, “misguided attempts to procure others’ approval and repair feelings of unworthiness and shame through displays of high achievement.”

It’s not just Silicon Valley

The rule that the way to (a) “procure others’ approval and repair feelings of unworthiness and shame” is (b) “through displays of high achievement” is as self-evident for many young people as the know-how that the way to (a) relieve hunger is by (b) eating.

Displays of high achievements just are how one earns love and respect.

Duh, what else is new?

When I feel bad about myself, I suck it up and start grinding to boost my self-esteem. Apparently, my opinion of myself depends on, and is sensitive to, how much I’ve hustled.

Performance is my coping mechanism for when I’m down.

And I know I’m not alone in this.

There’s one small problem:

Being perfect is a highly unrealistic achievement standard.

However, it doesn’t FEEL that way

My habit of linking my sense of self-worth to my accomplishments is taking its toll on me, and many of my fellow Millennials are facing the same struggle in their lives. Depressions, burn-outs, you name it.

Meritocracy is a nice ideal, but not a reality today. It’s also the reason we’re feeling more anxious about all aspects of our life than ever before. Philosopher Alain de Botton explains this link in his wonderful TEDTalk:

If you really believe in a society where those who merit to get to the top, get to the top, you’ll also, by implication, and in a far more nasty way, believe in a society where those who deserve to get to the bottom also get to the bottom and stay there. In other words, your position in life comes to seem not accidental, but merited and deserved. And that makes failure seem much more crushing.

If your life is ordinary, you have (i) failed and (ii) that’s your own fault.

Both these inferences are debatable.

- Does being average entail failure?

- Is it your own fault if you’re not perfect?

Moral authority

Before we answer those questions, how about you check out this “this is where we are” and I’ll grab another drink?

In today’s believed-to-be-meritocratic culture, everybody is expected to perfect themselves by striving to meet unrealistic achievement standards.

Where hunting for excellence was once a quirky hobby of those with ambitious tendencies, it is now a requirement for (being seen as worthy of) love and respect. Observes De Botton:

“Most people make a strict correlation between how much time and love — not romantic love, but love in general, respect — they are willing to accord us that will be strictly defined by our position in the social hierarchy.”

Relatedly, there is plenty of judgment towards the ‘average’. The injunction to make the most out of life and yourself has acquired a moral tone. Not doing so — “being basic” — is a vice.

In the second part of the article, I want to offer a different, counterintuitive perspective on fulfilling your potential.

“Will, you should go.”

My favorite scene from Good Will Hunting is the one where Chuckie, Will’s best friend living an “ordinary life” as a construction worker, tells Will he owes it to his friends to capitalize on opportunities they’ll never have, even if it means leaving without looking back. He confesses to Will that the best part of his day is a brief moment when he waits on his doorstep thinking Will has moved on to something greater.

The hoi polloi admit their jealousy of the hero’s talents. The star reluctantly accepts his own exceptional nature as he should.

It was the movie taking side.

“F**k mediocrity 😠.”

Be suspicious of what seems self-evident

If you’re still reading this far into a piece about self-improvement, the idea that fulfilling your potential is the correct way to live may seem obvious to you. Isn’t that what life is all about? To be our best selves?

Perhaps, but I want to invite you to zoom out here.

It’s easy to take the definition of “winning the game of life” that’s accepted in our society, and use that as a guide to living well without too much questioning.

Someone might have sold you the wrong plan.

Could it be that, for all you know, how you should live depends on who you are? And that, by extension, a life filled with accomplishments is not necessarily better than a life filled with savoring?

I want to warm you up to the heretical thoughts that [a] there are many ideals worth pursuing, [b] each of us needs to decide what he values most, and[c] there might be nothing to say one way or the other.

Moralizing is useless

In my view, the way in which fulfilling your potential has become tied up with (being considered worthy of) love and respect is a distorted frame that prevents us from seeing the key issue clearly.

We push ambition by shaming mediocrity and forcing a certain way of living on everyone.

When being perfect is so connected to being considered worthy of love and respect, we forget optimization is only one possible lifestyle.

As Will learned, setting out to fulfill your potential isn’t easy, and it ain’t free.

It’s time to question our hidden assumption: Is total optimization a good philosophy of life?

Go pursue your dreams 😃

When some intellectuals argue it is, they don’t issue their injunctives to fulfill your potential out of spite. The idea is not that it’s morally wrong — something making you less worthy of love and respect — to be content with average.

Their argument to steer clear of mediocrity springs from an altogether different well.

See how, for example, vulnerability-researcher Brené Brown analyzes her struggle with, as she calls it, living in the arena:

“We all have shame triggers: things that you could overhear someone saying about you that would be so painful that you don’t know if you could survive it. For me, these things really used to dictate my life. I engineered my career to be small and safe. I wanted to play right under the radar because I wasn’t willing to get myself out there and get criticized. The problem with staying small, however, is that it’s always connected to resentment. When we’re not using our gifts, and being in our powers, there’s always a price for that. When I realized this, I decided that I do want to live a brave life, that I do want to live in the arena.” — Brené Brown on the Tim Ferrisspodcast

Why fulfill your potential?

One thing immediately struck me as odd about Brown’s reasoning. It suggests “staying small” — not being ambitious — isn’t a normal, innocent, perfectly fine lifestyle choice. Rather, in 2019, mediocrity is a path someone only chooses out of “resentment.”

Everyone who slouches secretly has Will-Hunting-like psychological issues leading to self-doubt and fear, which explain their odd refusal to “live in the arena.”

Why would anyone think this? Why can’t it be old-fashioned laziness? A lack of enthusiasm about, as Venkatesh Rao puts it, “that nihilistic process of descending into valleys or ascending up hills till you get stuck, having an existential crisis, and then flailing randomly to climb out (or down) again?”

The idea here is that, as Brown says, “there’s always a price for [not using your gifts].”

Answer: your own happiness

What could she have in mind?

🎵 Hello [happiness], my old friend / I’ve come to talk with you again.🎵

People like Brown mean well 😃. They’re looking after your happiness.

Use your gifts! Achieve your potential! Be yourself! Maximize your talents! Go Will, go!

… And have a more fulfilling life in return.

Optimize yourself and your life, and you’ll be happy as a result.

😃 😃 😃 😃 😃 😃 😃

How much is enough?

There’s something to be said for this line of thinking.

The #1 regret of the dying has been reported to be “I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.” Powerful evidence for the belief that “being in your power” makes a positive difference.

Likewise, in his book Principles, billionaire investor Ray Dalio insists that having a great life requires “crossing a dangerous jungle” and isn’t compatible with “staying safe.” And in Good to Great, author Jim Collins argues few people attain superbness because it’s so easy to settle for mediocrity.

You have to honor at least some of your dreams, and that may require life-altering sacrifices like Will’s.

Sometimes a desire can be bad news.

How to live, the 2019 answer

This positive “go pursue your aspirations! 😃” trend is both similar to and different from “the f**k-mediocrity 😠” zeitgeist.

The latter is a coping mechanism to feel worthy in a culture of competitive individualism. Mediocre = you suck.

The former is a philosophy of how to live. Mediocre = we’re sorry to inform you that your life could’ve been better.

They give a different underlying reason in favor of fulfilling your potential: “Be your best self and be happy! 😃” versus “F**k mediocrity or be unloved 😠”.

That said, there are related:

Thanks to meritocratic developments, it seems like total optimization is the only game in town for how to live.

The common thread: fulfill your potential or be sorry.

What if Will was like The Dude?

Interestingly, this argument for fulfilling your potential is a means-end formula.

On both views, if you’re not pursuing your talents, you will, eventually, pay up in happiness. Get everything out of your life and yourself (means), for the sake of your own well-being (end).

This means-end structure invites the question: what if you’re not ambitious at all? You don’t harbor an ounce of the desire to get the most out of life. Not developing your gifts doesn’t impact your well-being in the slightest.

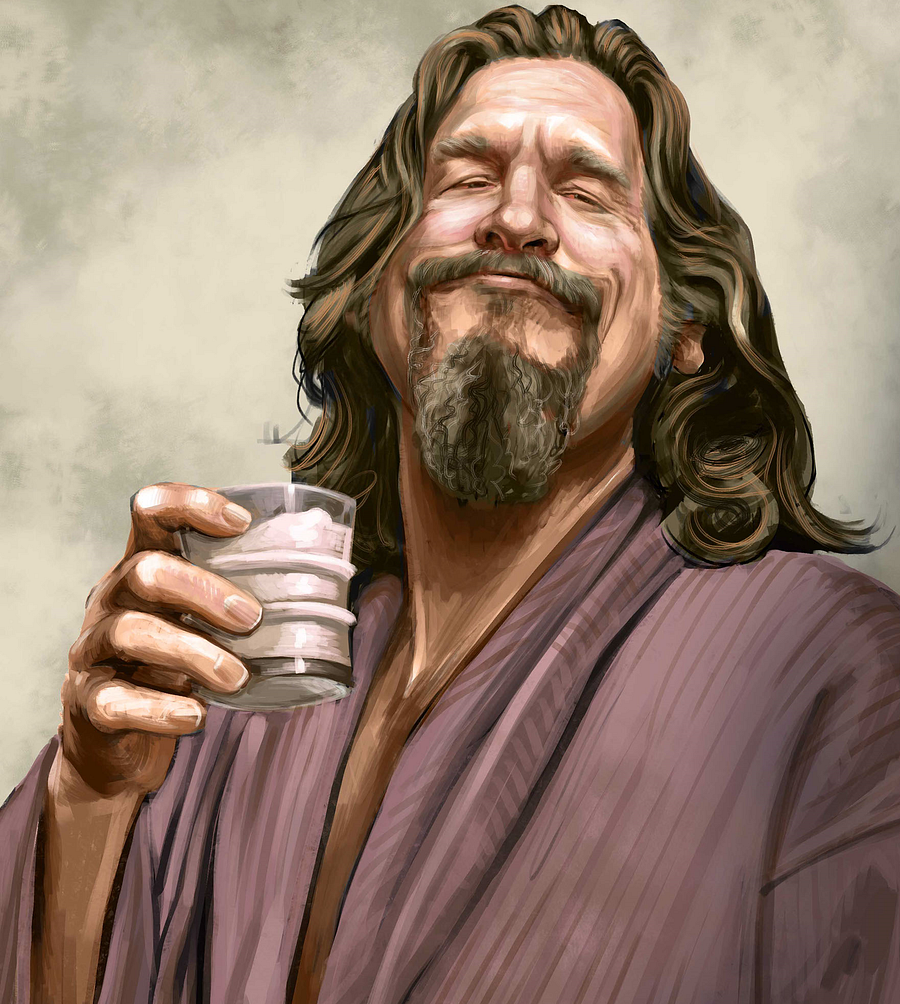

Let’s say Will Hunting had the character — the traits, desires, and values — of The Dude, from that other legendary film, The Big Lebowski. A carefree minimum-effort slacker who lacks any passion for self-improvement. Optimization-resistance, cannabis, and bowling are his priorities.

Even if you’re like The Dude, mediocrity makes you unhappy.

Should this Will still abandon his ‘ordinary life’ to pursue greatness? If those were his values, would the movie take the same side? Would it still be a good thing if Chuckie instructs him to leave in order to climb the mountain of achievement?

Happiness requires struggle

The 2019 answer seems to be: Yes.

And not because being mediocre makes you an inferior human being.

No, The Dude-Will should do it for his own sake. If he won’t attempt to squeeze everything out his extraordinary talents he’ll regret it. He will lie on his deathbed wishing he had had more courage.

Everyone has a duty to himself to fulfill his potential.

Can we choose?

In the meantime, the relationship between “f**k mediocrity 😠” and “be your best self! 😃” has changed.

The whole point of pulling them apart was to insist that pushing to maximize your personal growth was optional. It’s not necessarily bad or reprehensible if you approach life differently. It’s not something that makes you less deserving of love and respect. It’s just one of the available plans.

That was the crucial and for some people uncomfortable distinction that “f**k mediocrity 😠” overlooks.

But now we are told that getting the most out of life is not in fact that optional at all. Because if we opt for any other tactic in the game of life, we’ll regret that choice. Any other strategy except optimization guarantees misery. So actually, it is the only game in town. Be ambitious, or suffer.

The million-dollar question then becomes whether “go pursue your dreams! 😃” is right in its assessment of The Dude(-Will). Whether this entailment between not fulfilling your potential and unhappiness is universal.

Whatever floats your boat…

Thinkers as Brené Brown think this link does hold species-wide for us homo sapiens. That’s why, in their minds, optimizing yourself and your life is obviously the best plan there is. Hence choosing any other approach must be due to something like “resentment”. After all, who in his right mind would favor [staying small and being unhappy] over [growing big and feeling good]?

Is “staying small” really always connected to emotions such as “resentment”?

I don’t see why it would be. Perhaps many people just prefer to live that way as a matter of personality. Not because of bitter indignation.

If you claim such a decision does always spring from resentment, then what do you tell the nanny, the plumber, the janitor, Will’s friends?

Humans are wired differently. Not everyone needs total optimization for their well-being.

The Dude-Will would not have these deathbed-regrets of not fulfilling his potential. Rather than leaving his old life to do so anyway, it would be in line with his values to hold on to his ‘average’ existence. Therefore, that’s what he should do, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

Pragmatic resistance to totalizing thought in the domains of achievement and self-improvement needn’t be incompatible with flourishing.

Two views of human nature

Contrary to the doctrine that happiness requires struggle (for everyone), I subscribe to another view of human nature: we all have our deep-seated needs, each of us needs to decide what he values most, and there are no absolute truths about these issues.

If there are big enough differences in what two persons wish and value, then different things can be what they ought to do — fulfill their potential or not, leave or stay — with no absolute fact of the matter about who’s right.

In philosophical lingo: there are no facts about how someone has most reason to live that hold independently of what this person himself desires, cares about, and values.

When we face the deepest, toughest questions about how to conduct our lives, is the kind of fidelity we’re after fidelity to some alleged truth independent of us — “Humans must maximize their potential!” — or is it fidelity to ourselves?

Like gold transmuting into lead

This essay has been about how our culture narrows the gap between “f**k mediocrity 😠” and “be your best self 😃”.

At an ever faster pace, fulfilling your potential is moving towards the scary determination depicted in movies à la Whiplash. It’s also increasingly normal for optimization to go hand in hand with judgmentalness towards “ordinary people.” Less and less, meanwhile, it’s about just trying to achieve something cool.

Enthusiasm about ambition is turning, like gold transmuting into lead, into a nasty perfectionism required to receive, and feel worthy of, love and respect.

I worry about this a lot. It has nestled itself deep inside many young people’s minds. Including yours truly.

At the end of the tunnel, there is light

As more and more GaryVee-disciples wear t-shirts with F**k mediocrity, as judging people solely on their paycheck and Instagram followers becomes widespread, and the normalization of perfection continues, I wonder whether “basic” behavior will turn covetable.

In this climate, namely, having the courage to be ordinary becomes an attractive social niche to position yourself in.

Instead of signaling how much we’re optimizing, maybe we’ll signal how much we’re not optimizing.

The courage to be mediocre

I wonder whether, among us loud internet people, we’re beginning to see the beginnings of a countermovement to the ideology of maximizing yourself and your life.

A resistance to the normalization of perfection, spreading the opposite morale of Good Will Hunting: “You need not leave, you can have this ordinary, average, non-optimized life and be perfectly happy, and that’s okay.”

For instance, in a post aptly titled ‘Being basic as a virtue,’ tech blogger Nadia Eghbal imagines that if she were to pray to this counterculture pantheon, it might contain the gods of Basic, Mediocre and Degenerate:

Being basic is fist-bumping your neighbor at Barry’s Bootcamp for motivation before you both double the incline on your treadmill. It’s a resistance to intellectualism.

Being mediocre is turning down the combat difficulty on Red Dead so you can play through the game. It’s a resistance to hyper-optimization.

Being degenerate is watching Spongebob Allahu Akbar videos on YouTube and betting $5K that your friend can eat a five-pound gummy bear in one sitting. It’s a resistance to moral authority; you know most people find your behavior disgusting, and you love it.

To finish, let’s build on these suggestions.

How to be a normal human being in 2019, take two

Let’s make it normal again to chuckle at those who make a sport of having a totally optimized life. Let’s accept fat in the system. Let’s give ourselves permission to enjoy idle Monday mornings.

Let’s oppose seriousness, scorn and moralizing with non-attachment.

Let’s unapologetically ravel in non-productive sources of joy.

Let’s be Bad Will Hunting. Let’s name 80-hour workweeks a cultural transgression.

There can be happiness unconnected with struggle. You don’t need to deserve it. You’re good, spread the message.

Let’s make living in the arena optional again. Let’s stop treating displays of perfectionism and achievement as a condition for deserving love and respect. There’s more to life than optimizing it.

In the words of the #1 advocate of mediocrity Venkatesh Rao,

Can we get there? Yes we can, if we stop hustling so damn much.

Thanks to Kaspar, Vincent, and Josephine for helpful conversations