Humans aren’t bad, they’re not sinners, and certainly not evil.

It’s a common proclamation, people being immoral. At their core. Deep down. There are songs about it, books about it, tales about it, and religions based on it.

It lets us feel a little better about existing evil, and about the small unholy things we all do (yes, we know). Let’s all bathe in our rotten souls and absolve ourselves of responsibility.

Alas.

Scientists have stopped believing in the myth of the wicked human, and you should too.

What’s the evidence?

Whether we should believe in a theory — whether about bacteria, gravity, global warming, or human nature — depends on the evidence supporting it.

Of course, there can’t be empirical proof for man’s original sin, the fall, the disobedience of Adam and Eve, and things like that.

By contrast, arguments that are supposed to verify the corruption of our spirit, typically follow a two-step pattern.

- 1) In contrast to everyday circumstances in the 21st-century world, certain situations tap into the “pure” human, revealing him as he “really” is.

Here, defenders of humanity’s darkness typically take their cue from Thomas Hobbes’ thought experiment about “man’s state of nature,” move on to psychological studies by Stanley Milgram and in a Stanford Prison, and serve Hannah Arendt’s the “banality of evil” in their final act.

- 2) In these conditions, it turns out, humans behave as egoistic beats, thereby unveiling our rotten nature.

Let’s take a look.

Hobbes’ war of all against all

The most influential account of “pure” human behavior “in its natural state” was written by the 17-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes.

He set out to explain what historians now call ‘the agricultural revolution.’ When ancient humans formed the first societies, they had to start obeying laws. That’s a restriction of freedom. So why begin living in rule-governed communities nonetheless?

To account for this, Hobbes famously reasoned, the pre-society life of homo sapiens must have been a “war of all against all.”

Life in man’s state of nature was, in Hobbes’ memorable description, “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Without laws and the power to back them up, everyone would constantly steal and murder.

Hence we settled down, took up farming, and surrendered some freedom to governments. Submission to the rule of law was necessary to escape our beastly tendencies.

The Dutch primatologist Frans de Waal calls this the veneer theory: human morality is merely a thin overlay hiding an otherwise selfish and brutish nature. The threat of punishment as the only way to avoid a war of all against all.

Hobbes was wrong about pre-society life

Hobbes, writing 350 years ago, based his ideas about man’s state of nature on a mere thought experiment — not on data.

If only he had the information we do.

It’s simply not true that, without civilization to constrain us, human existence is a war of all against all. In the words of the famous anthropologist Jared Diamond, “hunter-gatherers practiced the most successful lifestyle in human history.”

Rather than “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short,” life before the agricultural revolution was better. Here’s historian Yuval Noah Harari summarizing cutting-edge archeological research in his world-renowned Sapiens:

Rather than heralding a new era of easy living, the Agricultural Revolution left farmers with lives generally more diɽcult and less satisfying than those of foragers. Hunter-gatherers spent their time in more stimulating and varied ways, and were less in danger of starvation and disease. The Agricultural Revolution certainly enlarged the sum total of food at the disposal of humankind, but the extra food did not translate into a better diet or more leisure. Rather, it translated into population explosions and pampered elites. The average farmer worked harder than the average forager, and got a worse diet in return. The Agricultural Revolution was history’s biggest fraud.

Social scientists Christopher Ryan and Cacilda Jethá draw the inescapable conclusion:

What Hobbes called “human nature” was a projection of seventeenth-century Europe, where life for most was rough, to put it mildly. Though it has persisted for centuries, Hobbes’s dark fantasy of prehistoric human life is as valid as grand conclusions about Siberian wolves based on observations of stray dogs in Tijuana. — Sex at Dawn: The Prehistoric Origins of Modern Sexuality

Milgram’s obedience experiments

“Okay Maarten, fair enough,” you say. “Hobbes’ speculation is demonstrably false.”

Your eyes narrow.

“But aren’t there empirical demonstrations of our innate scumbag-ness too? What about Milgram’s famous study of obedience?”

I’m glad you brought it up.

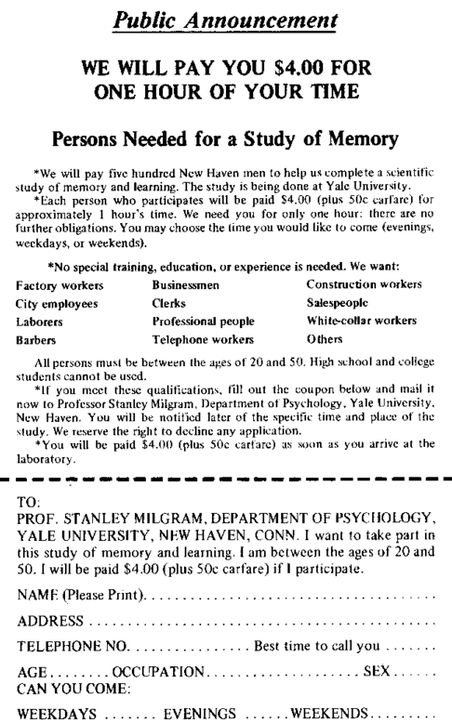

In 1961, in Milgram’s New Haven laboratory, a volunteer — dubbed “the teacher” — read strings of words to his partner, “the learner,” who was (supposedly) hooked up to an electric-shock machine in another room. Each time the learner made a mistake in repeating the words, the teacher was to deliver a shock of increasing intensity.

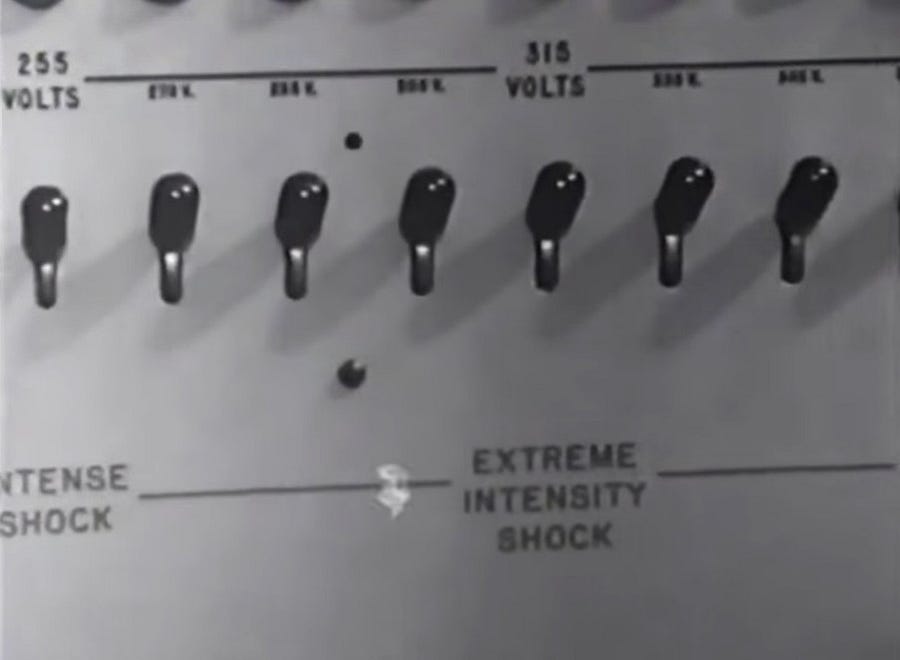

It started with 15-volts (labeled “slight shock” on the machine), but every time the student erred, an authoritative man in a gray lab coat ordered him to go further.

From 15 volts to 30 volts.

30 to 45.

And so on — up to the 450-volt switch, with the words “DANGER, HEAVY SHOCK” above it.

At 315 volts, the student pounded on the wall. At 450 volts, the learner would stop responding. Silence.

Did I just kill someone?

Of course, it was all a setup. The learner, unbeknownst to the teacher, was neither hooked up to a machine nor trying to memorize words. He was an actor running a script. Nonetheless, the results were shocking (pun intended).

Under the pressure of the authority of the man in the grey coat, everyone went on up to 315 volts.

That’s a jolt powerful enough to end a life.

Even worse, a whopping 65 percent went all the way up to 450 volts. That is, two-thirds of those good New Haven husbands and fathers appeared willing to electrocute strangers.

Proof of the veneer theory?

In short: Milgram got subjects to administer violent electric shocks to a subject they were supposed to be testing.

He himself suggested this indicates evil deeds are often the result of folks “just following orders.”

The capacity for evil lies dormant in everyone, ready to be awakened. Ordinary people, under the direction of an authority figure, would obey just about any order they were given.

Is the veneer theory right after all? Is civilization is only a thin crust we lay across the seething magma of evil?

What ‘Milgram’ really proves

‘Milgram’ has been used to explain atrocities from the Holocaust to the Vietnam War’s My Lai massacre to the abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib. “To a remarkable degree,” author Peter Baker notes, “Milgram’s early research has come to serve as a kind of all-purpose lightning rod for discussions about the human heart of darkness.”

Notwithstanding, in the past few years researchers have begun to argue that Milgram’s worp doesn’t prove what he claimed it does.

The Australian scientist Gina Perry spent countless hours investigating Milgram’s archives. “There I found,” she reports in her 2013 book Behind The Shock Machine, “the slow unfolding of a trial and error process in which Milgram refined, refined, and refined the scenario so that it would yield the results he wanted.”

Together with psychologist Nick Haslam, she discovered that, in fact, Milgram had conducted 23 different trials, each with a different scenario, script, and actors. Crucially, in these different setups, the levels of obedient responding varied enormously.

Milgram’s notorious finding represents just one of 23 experimental conditions he tried.

And a cherry-picked one at that.

When pooling all this data, an altogether different conclusion emerges:

This patchwork of experimental conditions, each conducted with a sample of only 20 or 40 participants, yielded rates of obedience that varied from 0% to 92.5%, with an average of 43%. Contrary to received opinion, a majority of Milgram’s participants disobeyed. — Nick Haslam, Steve Loughnan & Gina Perry, Meta-Milgram: An Empirical Synthesis of the Obedience Experiments

Clearly, the notion that we somehow automatically obey authority doesn’t account for the variability in obedience across conditions.

One out of twenty-three: there is no reason to think that ‘ready to do evil’ is our ‘default’.

And, on the risk of stating the obvious, the fact that most participants disobeyed undermines his entire conclusion.

If anything, the good is just as strong as the bad.

A sad denouement

The young Milgram, incidentally, knew what he was doing.

To the outside world, he described his findings as deep and disturbing truths about human nature. But in private, he doubted whether his experiments had anything to do with science at all.

“Whether all this staging refers to significant science or only effective theater is an open question,” he confessed in his diary.

Adding:

“I tend to accept the latter interpretation.”

The Stanford Prison Experiment

“Okay,” you admit, “I have to agree that behavior in an artificial scene carefully crafted to yield one very specific result might not tell us about our ‘defaults.’ After all, our ‘true nature’ is supposedly revealed in situations free from such manipulations.”

There was a brief pause as you plotted your next move.

“But surely the Stanford Prison Experiment isn’t a setup like that?! Surely it reveals the darkness of our souls?!”

Actually, the Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE) is an even bigger fraud.

What, again, is the Stanford Prison Experiment?

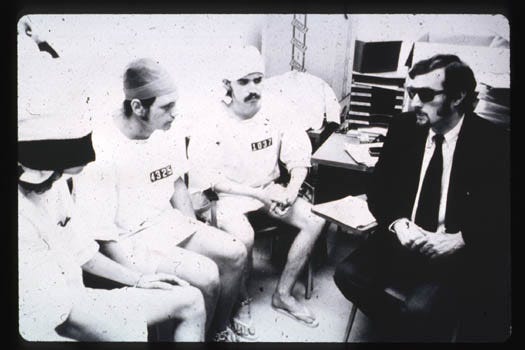

In 1971, Philip Zimbardo, like Milgram a young psychology professor, built a mock jail and stocked it with nine “prisoners,” and nine “guards” to investigate the psychological effects of perceived power.

When people have the possibility to torture and commit other normally-forbidden deeds, do they take it? Is lack of opportunity the only reason our everyday behavior is so nice?

The SPE suggested our ‘default’ behavior in a law-free zone might be Hobbesian after all. Zimbardo reported how guards enforced authoritarian measures and subjected prisoners to psychological torture. Prisoners passively accepted psychological abuse and, by the officers’ request, harassed other inmates who tried to stop it.

While the study was supposed to last for two weeks, it was shut down after six days. In that short time, five prisoners had been released because they showed signs of extreme emotional depression, crying, anger, and acute anxiety.

Since then, the tale of guards run amok and terrified prisoners breaking down one by one has become part of the collective unconsciousness.

SPE was a lie

The Stanford Prison Experiment, in which dead-normal students turned into monsters, supposedly proves Hobbes’ description of life in man’s natural state as “poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

It shares its alleged implication with Milgram: we all have a wellspring of potential sadism lurking within us, right underneath the surface.

And, parallel to Milgram once more, the SPE was a sham.

The participants were faking their reactions, Zimbardo had ulterior motives, rather than showcasing ‘default’ behavior the guards were instructed to be brutal, and it has repeatedly failed replication.

It has a host of issues, and there’s really no reason to take it seriously as a psychological study.

For an excellent breakdown on everything wrong about it, I’d suggest you read The Lifespan of a Lie.The Lifespan of a Lie

The most famous psychology study of all time was a sham. Why can’t we escape the Stanford Prison Experiment?gen.medium.com

The banality of evil

Defenders of the veneer theory have one more ace up their sleeve.

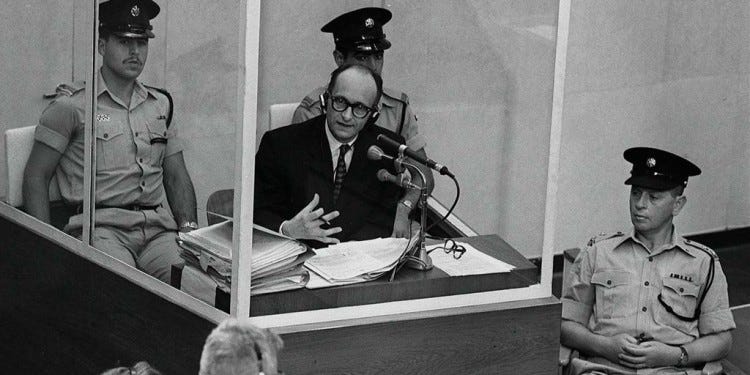

Coincidentally, as the first subject walked into Milgram’s New Haven lab, the most famous court case of the 20th century began its final week. Adolf Eichmann, responsible for the transport of millions of Jews during the Holocaust, stood trial in Jerusalem.

And the eminent Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt was there.

During the trial, Arendt found Eichmann an ordinary, rather bland, bureaucrat, who in her words, was “neither perverted nor sadistic,” but “terrifyingly normal.” He acted without any motive other than to diligently advance his career in the Nazi bureaucracy.

Eichmann was like those New Haven construction workers and hairdressers in Milgram’s lab. Like those Stanford kids in Zimbardo’s prison.

An average and mundane person.

Based on this, she proffered that those doing evil are not manifestly different from “normal” people. In the last sentence of her report, she named this “the banality of evil.”

Only in recent years have historians, once again, come to a very different conclusion.

Evil isn’t banal

From his behavior at the trial, Arendt inferred Eichman wasn’t perverse or sadistic. He was no immoral monster but performed evil deeds without evil intentions.

There is evidence to the contrary, though.

Before Eichmann was kidnapped by the Israeli secret service, the nazi Willem Sassen interviewed him for months. Sassen hoped that Eichmann would admit that the Holocaust was fake, but came away disappointed. “I don’t regret anything!” Eichmann assured him. “I will jump into my grave laughing knowing that I killed six million enemies of the Empire!”

Eichmann boasted of his accomplishments, worried that he hadn’t done enough, and justified his role and the genocide.

In light of this, many scholars conclude Eichmann’s performance in Jerusalem was a successful deception. The true Eichmann wasn’t mundane, or without ideology, or merely following orders.

He was a fanatical anti-Semite.

All you need to know

To, finally, sum up: Hobbes’ concoctions about man’s state of nature are fantasies. Milgram and The Stanford Prison Experiment were theatre, and to maintain they reveal any truth about human nature is absurd. And the banality of evil is a misunderstanding.

Turning ordinary people into monsters requires a hell of a lot more than just peeling away a thin layer of pretention.

Compassion and social instincts are very much a part of human nature as well. There’s no reason to uphold our bad side as the “real self.”

As it turns out, ‘by default’, when disaster strikes and rules are suspended, we behave in line with the better angels of our nature. For instance, researches studying Hurricane Katrina have often described how “prosocial behavior was by far the primary response to this event, despite widespread media reports [to the contrary].”

In his study of human nature, Wait But Why accordingly characterizes empathy as “the superpower that, above [everything else], makes us human.”

The opinions of those who shrug at this and somehow just know human nature is rotten shed much more light on the prejudices of their defenders than on humanity’s soul.

Why does all of this matter?

It matters, because you have the power to radically change your identity.

Humans grow into the stories they tell each other and themselves. As Carl Jung said: ideas have people, not the other way around.

The natural world is what it is, and will behave the way it behaves no matter what we think. But it’s not so simple with human beings. How we act depends fundamentally on who and what we believe we are.

If you actively — counterintuitively perhaps — assume the good in people, and if enough people are brave enough to take this leap, we can organize this thing called living together in a totally different way.