In the good old days, philosophy existed for the sake of human beings. To address our deepest needs, confront our most urgent perplexities, and elevate us from misery to flourishing.

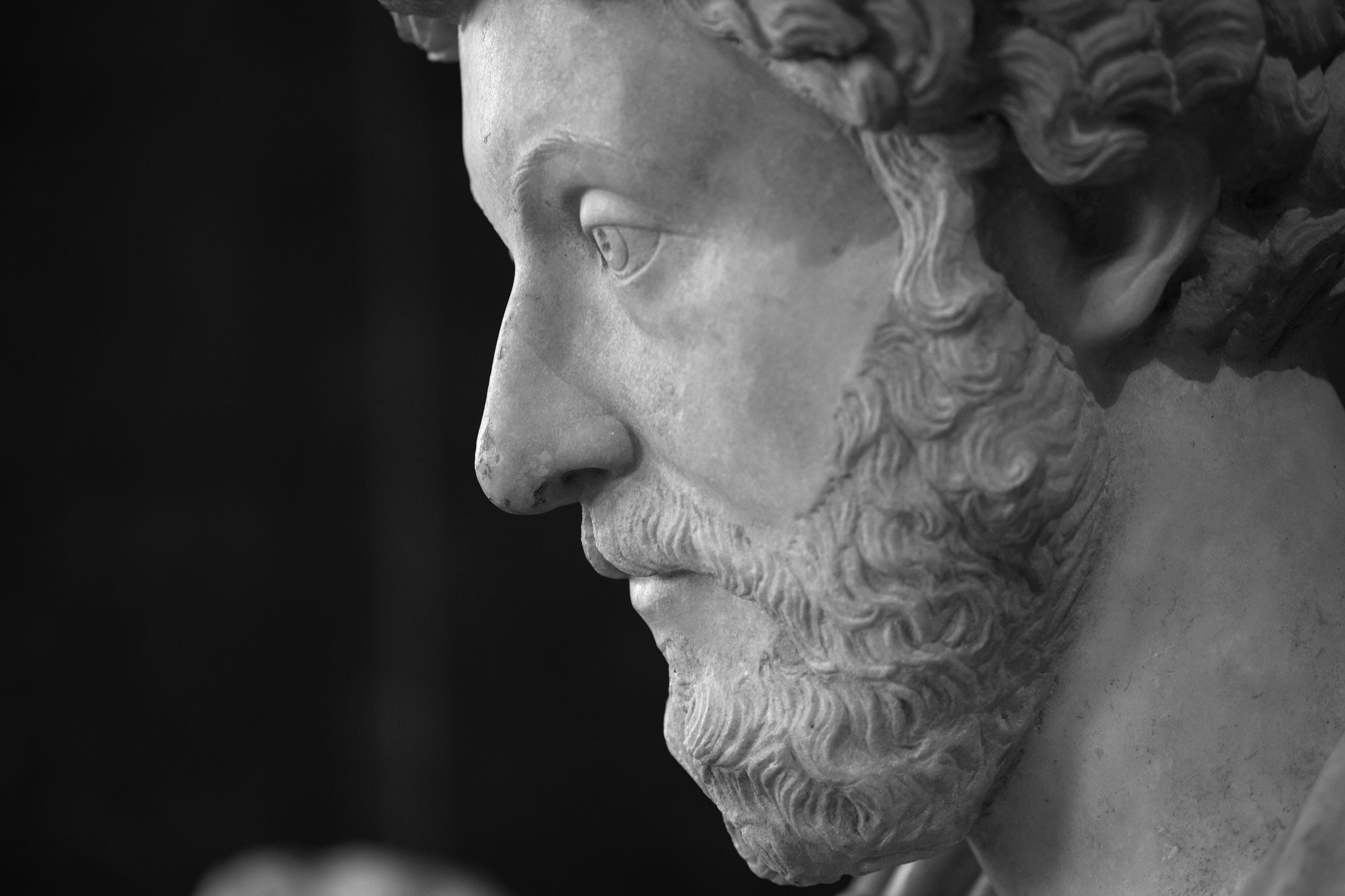

It’s with great fondness that I recall the days of Seneca and Marcus Aurelius, except for the fact that I wasn’t there.

In those days, the main aim of ‘schools’ of philosophy — of which Stoicism was one, Epicureanism another — was to develop the character of the student. It was an operating system that had been tested on the front lines, literally in the case of Marcus Aurelius, and metaphorically, in the case of Seneca, in other high stakes environments, like the Senate.

Philosophy designed for doers.

Marcus Aurelius, emperor of the Roman Empire, the most powerful man on earth, sat down each day to write himself notes about humility, self-awareness and the meaning of life. And Seneca was simultaneously an esteemed playwright, one of the wealthiest people in Rome, a famous statesman, and an advisor to the emperor Nero (who ordered Seneca to kill himself).

Fascinatingly, the teachings of such Stoic sages is immensely popular these days. Tim Ferriss uses it as his “personal operating system” and, of course, Ryan Holiday talks about it all the time as well.

In this essay, I’ll reveal that Stoicism had much more to offer — stuff that Tim and Ryan don’t even touch upon.

The dichotomy of control

We mainly associate Stoicism with cultivating an eery sense of calm in the face of, well, everything. In many minds, Stoicism is linked to a Dexter-like affective independence of life-events that sometimes overdoes it.

Indeed, many Stoics emphasized that because ‘virtue is sufficient for happiness’, a wise man would be emotionally resilient to misfortune.

And according to philosopher William Irvine the ultimate goal for Stoicism was “tranquility”, which, he says, was defined as “the avoidance of negative emotions to the extent possible.”

Here the most well-known Stoic teaching comes in. The first step you can take to achieve this, namely, is to strictly divide the world into things — or efforts — that are up to us, and things — or outcomes — which aren’t.

Ultimately, you don’t control the outcome. So don’t attach your happiness and self-esteem to it.

You don’t need to worry about the things you have control over, because you have control. You don’t need to worry about the things you have no control over because there’s nothing you can do about those.

Stoicism is an effective way to regain the sense that we have a grip on our lives. To reclaim the gap between stimulus and response.

That’s not all, though.

Feeling joy

Practicing the dichotomy of control is what Stoicism is best known for, but its operating system has other aces up its sleeve. Another practice it recommends is ‘negative visualization’ — imagining how things could be worse. Allow yourself flickering thought about what it would be like were your biggest fears to come true.

If you assume that what you fear may happen will certainly happen, measure it in your own mind, and estimate the amount of your fear, you will thus understand that what you fear is relatively insignificant, the Stoic predicts.

Negative visualization is a neat psychological trick that lowers levels of expectations and thereby increases your happiness (which, according to my grandma and her cat, equals the sum of reality minus expectations).

In his famous Letters to Lucilius, Seneca many times counsels that we should constrain our desires to increase our delight:

“Riches have shut off many a man from the attainment of wisdom; poverty is unburdened and free from care … Men have endured hunger when their towns were besieged, and what other reward for their endurance did they obtain than that they did not fall under the conqueror’s power? How much greater is the promise of the prize of everlasting liberty, and the assurance that we need fear neither God nor man!Even though we starve, we must reach that goal.”— Seneca, Letters to Lucilius

As this passage indicates, it’s not only the “avoidance of negative emotions” that concerned Stoics. It’s not for nothing that Seneca advises his cousin Lucilius to make this his number one priority:

“Above all, my dear Lucilius, make this your business: learn how to feel joy.” — Seneca

Apparently, Stoicism is not just about conquering the negative, but also about maximizing the positive.

Was Seneca a mystic?

“Believe me,” Seneca writes in the same letter in which he hails “everlasting liberty,” “real joy is a stern matter … The joy of which I speak, that to which I am endeavoring to lead you, is something solid, disclosing itself the more fully as you penetrate into.”

There are other, temporary, joyful moods, but they are not “a cheerful joy”, according to Seneca. Not real joy.

If your intuitions are like mine, you’ll respond that the idea of non-cheerful joys doesn’t make sense. However, if we recall the Stoics’ emphasis on the distinction between what you can control and what you can’t, it seems that what Seneca means is that pleasures whose source is purely internal are the only genuine ones:

“True happiness is to enjoy the present, without anxious dependence upon the future, not to amuse ourselves with either hopes or fears but to rest satisfied with what we have, which is sufficient, for he that is so wants nothing.” — Seneca, Letters to Lucilius

He who experiences true joy, wants nothing more than this, now. The present, in itself, suffices.

Disregarding the times that I beat my siblings at Mario Kart, when I dig in my memory and recall my other deepest moments of joy, I notice they didn’t have a particular object. There wasn’t one thing that caused the happy feeling. It was a deep realization that life is fantastic. This experience might have been induced by one particular event, but it wasn’t directed at one thing. Everything revealed itself as truly amazing.

“How could I only see this now? Why was I so ignorant?”

In these episodes, I feel like life is merely reminding me of the facts and bringing me back to my natural state of happiness.

“If some obstacle arise, it is but like an intervening cloud, which floats beneath the sun but never prevails against it.” — Seneca, Letters to Lucilius

In bad times, we needn’t defeat the demons. Rather, simply go to the window, pull out a rag, and start cleaning. Just clean. And soon enough, light enters naturally, taking the darkness away. Bringing you back to the default state.

Does this sound rare, or unrealistically psychologically demanding, to you? The mystic needn’t disagree. He’ll assert that genuinely happy people are much rarer than one supposed. “You are not really happy,” replies the mystic, “and no one knows it better than you. Beyond all your shallow pretenses and invented activities, you see your own emptiness. You can try to kid yourself, but you can’t kid your anxiety, your burn-outs, your irritability, and your sleepless nights.”

According to mystics, these mental states are the rule, not the exception. You feel good not because the world is right, but your world is right because you feel good. Your True Self can no more be negative than an angel can be impure.

This is Seneca applying the distinction between what you can control and what you cannot to the feeling of happiness:

“Therefore I pray you, my dearest Lucilius, do the one thing that can render you really happy: cast aside and trample under foot all the things that glitter outwardly and are held out to you by another or as obtainable from another; look toward the true good, and rejoice only in that which comes from your own store. And what do I mean by “from your own store”? I mean from your very self, that which is the best part of you.” — Seneca, Letters to Lucilius

Linking Seneca’s distinctions between “[non-true] joy” and “true joy that comes from your very self”, invites the question of whether Seneca was one of these mystics!

“[Pleasures] are not substantial, they are not trustworthy; even if they do not harm us, they are fleeting. Cast about rather for some good which will abide. But there can be no such good except as the soul discovers it for itself within itself. Virtue alone affords everlasting and peace-giving joy.” — Seneca, Letters to Lucilius

This robust feeling of reason-less bliss sounds to me like the #1-prize of the game of life. What could be better than feeling great every single minute?

And yet, something about the very idea of everlasting cheerfulness doesn’t feel quite right.

Joy versus true joy — does it exist?

So far, we’ve been investigating two core claims: (1) If your happiness is caused by something that might be taken away from you, is external to you, then it’s not real joy. (2) Luckily, then, there “everlasting joy” to be found, but only insofar “as the soul discovers it for itself within itself”.

I’ve been meditating for over 10 years, and one of my favorite mantras is that being happy for a reason is actually a form of pain. The happiness depends on the source, and if there’s a change on that front, your happiness disappears. It’s contingent. And since nothing is permanent, this source of feeling good too shall fade. Hence, your present happiness it’s just suffering in disguise.

The delight is merely apparent delight, because it has the wrong origin. It has the wrong origin because it’s contingent on something that is not permanent.

This is the argument.

It divides me deeply.

Sometimes I think it’s extremely lame. Life is about desiring and succeeding or failing and falling down and climbing back up and being fucking angry and losing and then being ecstatic when you reach the top.

Loved ones will die but are a significant, and legitimate, source of joy.

If you think these feelings are unreal, go and live, make a choice, fall in love, do something, get hurt, crawl back up, and you will change your mind.

A lot of good things in life come from contrasts. Can I genuinely be content if I’ve never felt sad? Perhaps, but not in the same way. Experiences of loneliness make subsequent feelings of comradeship deeper.

The idea of everlasting cheerfulness seems to miss out on this. It comes across as naive.

Paradoxically, it also sounds like it gets something super profound uniquely right. Like it explains what I feel in these ecstatic moments: there really is a more fundamental truth about the peak of unworried living. Observes Aldous Huxley:

“It is because we don’t know who we are, because we are unaware that the Kingdom of Heaven is within us, that we behave in the generally silly, the often insane, the sometimes criminal ways that are so characteristically human. We are saved by, we are liberated and elightened, by perceiving the hitherto unperceived good that is already within us, by returning to our eternal ground and returning where, without knowing it, we have always been.” — The Perennial Philosophy

On some interpretations —The Third Jesus, to name one — that’s the same thing Jesus meant when he said

“The kingdom of God does not come with observation; nor will they say, ‘See here!’ or ‘See there!’ For indeed, the kingdom of God is within you” (Luke 17: 20–21)

William James, the famous American psychologist, harmonizes mysticism and mysticism like this:

“Personal religious experience has its roots and centre in mystical states of consciousness … I think I shall at least succeed in convincing you of the reality of the states in question, and of the paramount importance of their function.” — The Varieties of Religious Experience

And recall the passage from Seneca quoted earlier: “There can be no [good which abides] except as the soul discovers it for itself within itself.”

If that still sounds too shady for you, here’s our own Zat Rana:

“My starting point is ‘something’ … So: What is this “something”? Different people call it different things, but it’s the only objective thing that exists: Consciousness … While we can think of it as objective, it is only ever experienced as change, and it can’t be pinned down in language without distorting it … . I think that Consciousness is primary … Truth itself, or Consciousness, is infinite.” — The Void and I: A Story About Everything

Now, I’m no theist, nor a scholastic scholar, but I think these people were too intelligent, and the subject matter too important, to not investigate their suggestions.

Here are two facts:

One: my goal is to become a happy, pleasant, enlightened human being. Two: some mystics report a blissful state of pure Consciousness.

Could it be that the only way to achieve unshakable success and experience true happiness is through knowing the true nature of myself and the universe?

Is there a kingdom of God, or Truth itself, or Consciousness with a capital C, within each of us?

Like to read?

Join my Thinking Together newsletter for a free weekly dose of similarly high-quality mind-expanding ideas.